An original article by Decision Free Solutions.

The approach of DFS in Action

For the full article in PDF go here.

Management summary

In this document the approach of Decision Free Solutions has been used to analyse and explain the results and performances of several pioneering methods and organisations as found in management literature. These concern both successful organisations which started with a new way of working, as well as those who arrived at a new way of working following a transformation. This document also demonstrates how DFS guidelines can be used to improve upon existing procedures.

Several aspects of a new way of working are addressed, including self-managing teams, hierarchy without hierarchical decision making, the tasks and selection of leadership-roles, the importance of purpose, recruitment based on perceptiveness, and the avoidance of rules, procedures and protocols. Organisations featuring in this document include Buurtzorg, Haier, Patagonia, K2K Emocionando, Spotify, Smarkets and Freitag.

This document demonstrates both the validity of the DFS concepts — the need to minimise decision making and the importance of perceptiveness — as well as its practical value in guiding organisational and procedural changes towards the utilisation of expertise. It makes the greater point that the future of work must not rely on “experimentation”. Existing organisational examples can be adapted to local circumstances by applying the underlying principles.

About Decision Free Solutions

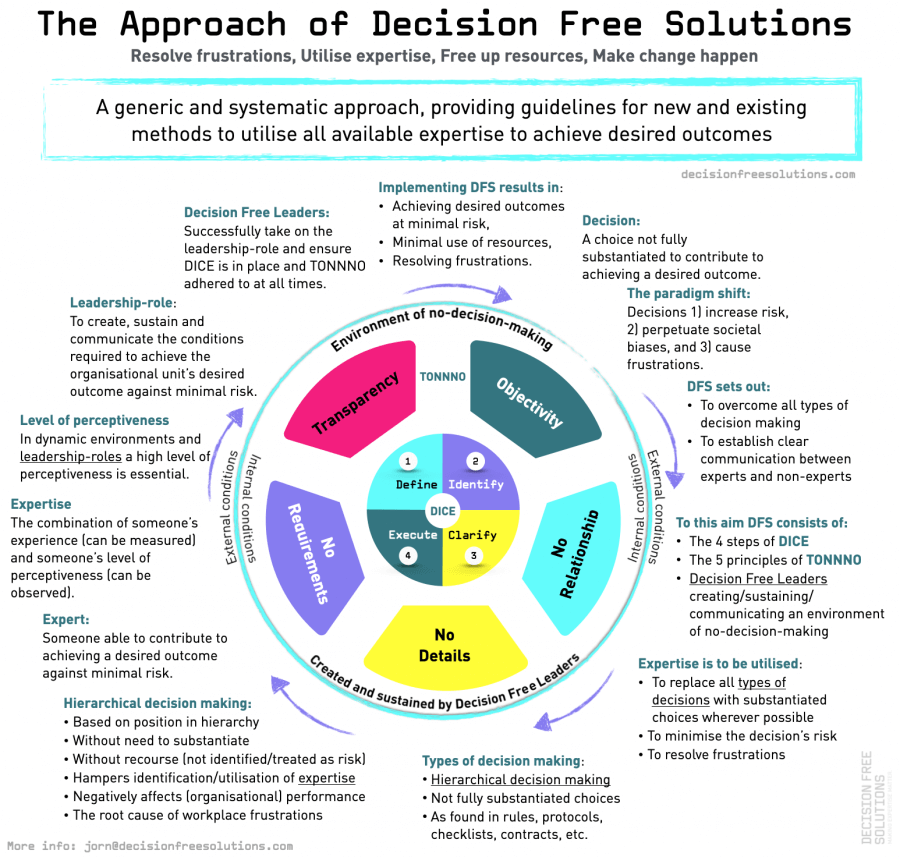

The approach of Decision Free Solutions (DFS) is a generic and systematic approach, providing guidelines for new and existing methods to utilise all available expertise to achieve the goals you believe in. Implementing the approach of DFS results in i) Achieving desired outcomes at minimal risk, ii) Minimal use of resources, iii) Resolving frustrations.

The approach of DFS clarifies a “decision” as a choice not fully substantiated (and thus increasing risk) and sets out to overcome two central challenges in optimally utilising expertise:

- The prevalence of all types of decision making preventing the use of expertise (hierarchical, and as found in rules, procedures, protocols, checklists and contracts)

- Ensuring the clear communication between experts and non-experts to prevent mechanisms of control and decision making kicking in

To do so it provides guidelines in the form of four steps (DICE), five principles (TONNNO), the role of the Decision Free Leader, as well as clear definitions of crucial terminology. The approach has been introduced in [1]

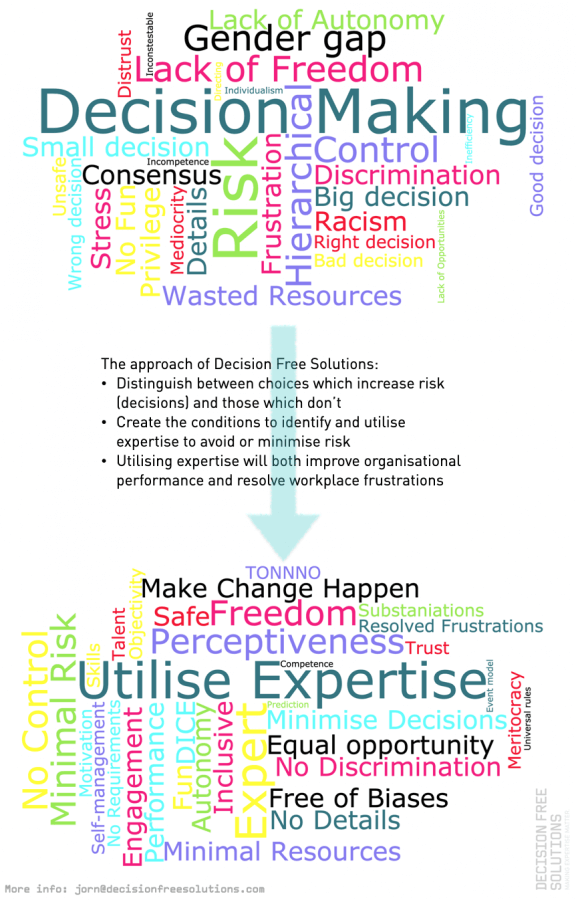

A summary of the approach of Decision Free Solutions is provided in Figure 1. In Figure 2 the resulting transformation away from decision making and towards the utilisation of expertise is depicted by way of word clouds.

Figure 1. Graphical summary of the approach of Decision Free Solutions.

Figure 2. Implementing the approach of Decision Free Solutions results in a shift or transformation away from decision making towards the utilisation of expertise.

A Decision Free Organisation: Buurtzorg

Buurtzorg’s single basic organisational principle

Buurtzorg is a highly successful organisation that has attracted a lot of attention. It features prominently in Frederic Laloux’ “Reinventing Organisations” and in “Corporate Rebels: Make work more fun” [2,3].

Buurtzorg is a Dutch organisation founded in 2006 whose name translates to “neighbourhood care”. Buurtzorg sets out to provide client care from a holistic perspective. The organisation employs almost 15.000 nurses, with an office of no more than 50 people and 20 coaches. Buurtzorg’s results are extremely positive across the board: financially, quality of care (patient satisfaction), and job satisfaction.

It is almost easier to define the organisation by what it doesn’t have: managers, unnecessary policies, an HR department, marketing staff, complicated titles, and lengthy job descriptions [3].

Buurtzorg consists of over a 1’000 self-managing teams supported by training, coaches and an IT-platform. Buurtzorg’s teams are highly autonomous. Each team is in charge of providing care to their customers, but also everything else. From deciding which patients to serve, intake, planning, scheduling, recruitment, which doctors and pharmacies to reach out to, individual and team training to renting and decorating their office.

For all its success, its sophisticated IT platform and a way of working honed over more than a decade, Buurtzorg’s way of working can be reduced to the application of a single basic organisational principle: minimise decision making through the utilisation of expertise.

Founder and CEO Jos de Blok started Buurtzorg because: “We’d had enough of managers determining how people should do their work. I was convinced that true professionals know when and how to apply their competencies, without the need for managers. […] At Buurtzorg we have no artificial hierarchy; all decisions are made after consultation. If we cannot optimally use our people’s talents, this is a significant waste. Our professionals come up with new ideas. They generate thousands of ideas every day.”

Buurtzorg’s way of working

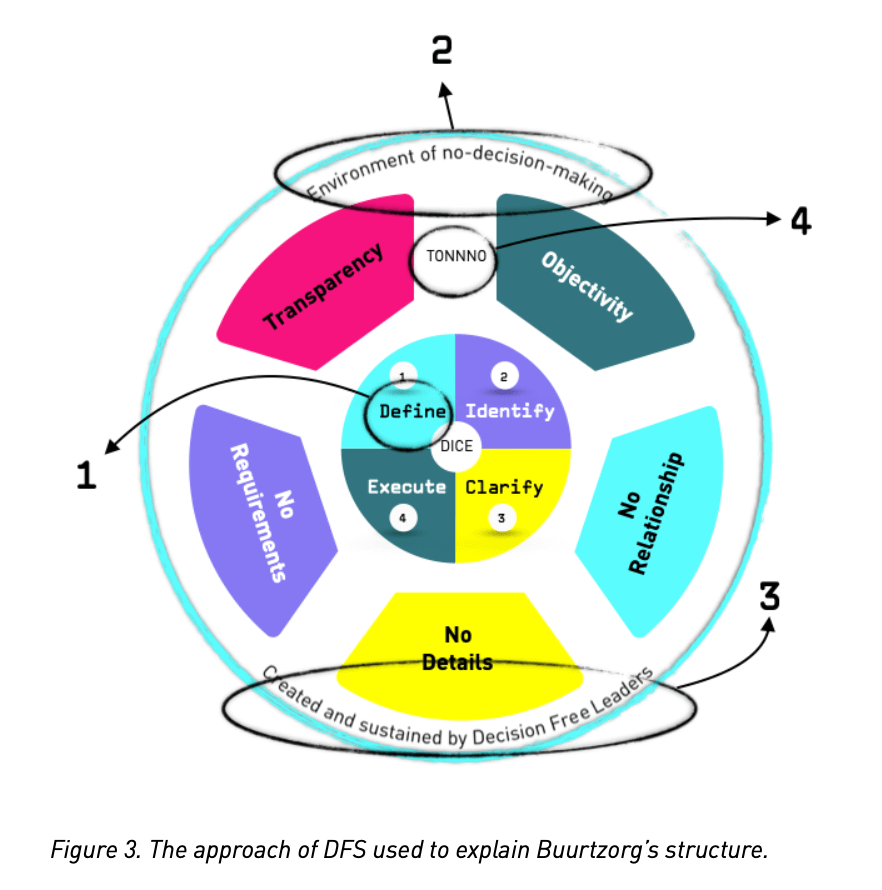

Buurtzorg’s way of working can be explained as follows (the numbers refer to Figure 3):

- Purpose — To utilise expertise the organisation’s desired outcome is to be transparent to all involved. This is the first step of DICE (Define). In the case of Buurtzorg this is relatively easy, as its self-managing teams are very homogenous, consisting out of qualified nurses. Still, having a clear organisational purpose is essential.

- An environment of no-decision-making — Utilising expertise means that most choices that will be made can be fully substantiated. Buurtzorg tries to avoid making choices which are not fully substantiated (a.k.a. decisions). Its office performs certain administrative, legal and financial tasks and provides support, but it does not produce directives, rules or protocols. Its coaches don’t make decisions for the teams, and the team meetings are set up to assure everyone’s expertise is brought to the table and decision making is consequently minimised (both of which will be discussed below).

- Decision Free Leaders — In DFS Decision Free Leaders are to create, sustain and communicate an environment of no-decision-making. In Buurtzorg this environment (the organisation’s culture) is guarded by its CEO, the coaches, and during team meetings by the team-elected “facilitator”. The CEO’s role will be discussed further below.

- Transparency and objectivity — One central challenge identified by DFS in optimally utilising expertise is establishing clear communication between experts and non-experts. This applies to communication within the teams, between the teams, and between the teams and the office. In the case of Buurtzorg this challenge is considerably reduced because of its homogenous workforce (qualified nurses). But a transparent and objective way to measure performance is still pivotal. It allows the objective identification of one team’s performance to the benefit of all the others, it allows coaches to become proactive in providing the support where it appears to be needed most, and it does away with the need for mechanisms of organisational control. At Buurtzorg this transparency and objectivity is achieved through a comprehensive IT system providing real-time insights into a range of (also performance) parameters. It also allows the teams to communicate with one another, offering necessary support and insight.

Buurtzorg’s coaches and meeting process

Buurtzorg’s teams look after themselves in practically all aspects, but they are not simply left to their own devices. An essential element of the support structure provided by the office is coaching. Regional coaches play a crucial role in ensuring the self-managing teams remain on track. These coaches are invaluable, but they have no decision-making power.

From Laloux’ book: “[Coaches] are not responsible for team results. They have no targets to reach and no profit-and-loss responsibility. […] The coach’s role is to let teams make their own choices, even if she believes she knows a better solution. The coach supports the team mostly by asking insightful questions and mirroring what she sees. The starting point is always to look for enthusiasm, strengths, and existing capabilities within the team” [2].

In the same book also Buurtzorg’s meeting process is described [2]:

- There is no boss. No one can call the shots or make the final call.

- The group begins by choosing the meeting’s facilitator.

- The agenda is determined on the spot.

- The facilitator can only ask questions, not make statements/suggestions/decisions.

- All proposals are listed on a flip-chart and reviewed/improved/refined one-by-one.

- Each proposal is put up for a “group decision”.

- The basis for decision-making is not consensus, but for nobody to have a principled objection (in recognition of the fact that the “perfect solution” might not exist)

- Any proposal adopted this way can always be revisited if new information becomes available.

- If a team gets stuck, they can request external facilitation at any time, and also turn to other teams for suggestions (e.g. through the internal IT platform).

Buurtzorg’s meeting process may since have been evolved, but there are some important observations to be made here. By avoiding hierarchy (no team leader, facilitator elected by the team, no single person setting the agenda), by assuring the topics for discussion are transparent to all, and by accepting proposals only when no principled (substantiated) objection is made the available expertise is fully utilised and decision making minimised.

The role of Buurtzorg’s CEO

In DFS the responsibility of all leadership-roles throughout any organisation is always the same. It is to create, sustain and communicate the conditions required to achieve the organisational unit’s desired outcome at minimal risk [4].

Buurtzorg’s CEO — Jos de Blok — was also the organisation’s founder. In an interview for a national newspaper about leadership he shared that within the organisation “leadership” is not a much-discussed topic. Jos de Blok’s main organising principle, which is rooted in his own experience as a regional director of two nursing care organisations, is that managers should not have too much to say, as they readily get in the way of those who do the actual work. When asked directly whether he sees himself as the leader of the organisation, he says no. He isn’t needed for any of the organisation’s activities.

But he then goes on to state: “My role involves staying in touch with collaborative partnerships in twenty-five countries. On top of that I guard the principles, the flat organisation without the unnecessary bureaucracy I have always envisioned. It is all very precarious. If you let go of the principles, Buurtzorg becomes a traditional organisation within years.”

From DFS’ perspective, Jos de Blok successfully takes on the organisation’s most visible leadership-role through communicating his beliefs and principles. He does this in interviews, in management-literature, in a documentary and in many other, more subtle, but by no means less visible means. He doesn’t wear suits, he doesn’t have an executive office, his title on his LinkedIn profile is two dashes (“- -“ ), and he communicates his views through sharing and commenting on social media posts of others.

It could be argued that Jos de Blok is very much the personification of Buurtzorg’s culture, and vice versa the organisation’s culture is a reflection of Jos’ beliefs. Consequently, Buurtzorg’s main challenge may be sustaining its culture once its founder steps down.

Why K2K is so successful at organisational transformations

K2K’s New Style of Relationships

Koldo Saratxaga, the founder of K2K Emocionando, began by implementing organisational changes in a technically bankrupt manufacturer of carriages and stagecoaches back in 1991 — resulting in an averaged annual growth of 24% for 14 consecutive years. The impact of his approach began to take flight with the creation of the K2K Emocionando-team in 2006. K2K has since transformed 70 dysfunctional organisations across diverse industries [3].

The approach, or perhaps better “outcome,” of the efforts of the K2K Emocionando-team is called NER: New Style of Relationships. In the words of Pablo Aretxabala: “NER is about making people effective and the true center of organisations — working with absolute transparency, trust, freedom and responsibility. Those that have implemented NER have no hierarchical structure of any kind, no elements of control, no power struggles, no dark zones. Instead we have self-managed teams, responsibility, commitment, initiative and shared decision-making.”

The steps taken to turn organisations around, and its view on leadership and decision making as shared here, are all taken from [3]. They are provided with comments from DFS’ perspective. To copy K2K’s measures one-to-one is unlikely to lead to success. By explaining the underlying principles they can be adjusted, however, to suit local circumstances. Sometimes they may even be improved upon.

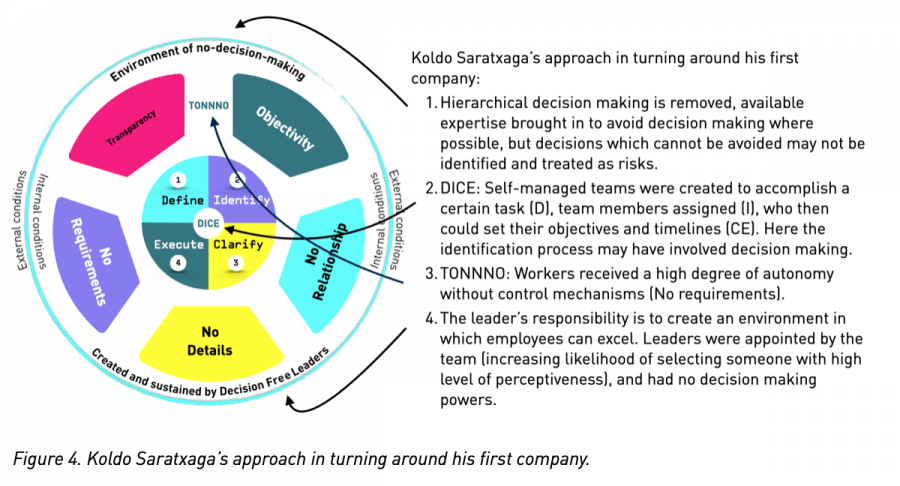

Organisational changes made to turn a near-bankrupt company around

Back in the early nineties Koldo Saratxaga became the “General Co-ordinator” of a company whose survival was in the balance. To survive, and thrive, Koldo set out to create an environment that was “adaptive, resilient and responsive” to a world that was constantly changing.

Several of the measures taken (from [3]):

- Getting rid of the hierarchical pyramid with all its command-and-control mechanisms, and replacing it with a flat organisation which consisted of multidisciplinary, self-managed teams — In DFS hierarchical decision making is to be overcome. The use of self-managed teams does away with much of the hierarchy, and thus starkly reduces hierarchical decision making as well. DFS stresses that “hierarchy” in itself is not the problem (“hierarchical decision making” is), and that also in the case of self-managed teams the remaining decision making within the teams (e.g., in meetings) is to be minimised as well.

- Team members were assigned to projects — Assigning team members to projects is, potentially, a form of decision making (it may violate the principle of “no relationship” if someone is merely told to take on some task by someone else). In this particular case “assigning team members” may merely have been part of making the transition in the first place, and not how project teams are created today. From the text it is not clear.

- Team members were able to elect their leaders — In DFS the leadership-role is responsible for creating the conditions in which all team members can bring their expertise to the table. To take on this role successfully requires a high level of perceptiveness [4]. This can’t be measured, but it can be observed. Which is what people working together do. Consequently, to have “team-appointed leaders” is a very powerful mechanism. With a few caveats. 1) The team may be newly formed and too few observations have been made to base an appointment on, 2) in absence of any guidance the team members may make the mistake of identifying the “specialist” instead, and 3) there may be no one in the team who is truly suited to take on the leadership-role.

- Manufacturing and service facilities were relocated to one floor — DFS identifies communication between experts and experts-in-something-else as one of two major challenges. To improve communication between various disciplines increasing the frequency of interaction contributes to better alignment and increased transparency.

- The self-managed teams could set their own objectives and time schedules — Having Defined a team’s desired outcome, and having Identified the employees who can help achieve it, then it are, logically, the same people who are to Clarify how this outcome can be achieved. The team sets the objectives and makes the plan.

- Most of the old control mechanisms were removed — If the organisational culture provides the conditions to utilise expertise — clearly defined goals, minimised decision making, perceptive team leaders, teams setting their own objectives — responsibility and accountability automatically follow. Control mechanisms are both no longer needed, and also impossible to implement (what do you want to control?).

- All privileges were removed — These included no private offices, no special dining rooms, no reserved parking, no bonuses or incentives for individual performance, and no special access to information. These measures contribute to a better communication, a “safer” environment (see next point), and greater transparency. The concept of individual bonuses and incentives is especially problematic — and absent in DF Organisations — as it falsely assumes that 1) performance hinges on the individual instead of the team, and 2) that individual workers can be influenced/motivated to “add more value” if you promise extra financial compensation.

- Evaluation was based solely on team performance — To utilise expertise (hierarchical) decision making is to be avoided. But expertise should also be put on the table, and thus the culture must also be “safe” and encourage everyone to speak up and share ideas (e.g., by removing remaining symbols of hierarchy so that everyone feels equal). Individual evaluations are non-sensical as someone’s performance is dependent on a range of factors the individual has no control over. Evaluations based on team performance, on the other hand, contribute to a safe environment.

- Make objectives and results known throughout the organisation — This was done both for the objectives and results of the individual teams as well as those of the organisation as a whole. The (financial) information of how the organisation is doing is important as all the teams operate within this organisation. It is essential information in DFS’ Define-step, as it of great importance in determining a team’s objectives and the availability of the resources that would be required. It is also essential to share real-time performance information to prevent mechanisms of control to kick in (such as meetings, progress reports, and sharing a lot of information).

K2K and leadership

In DFS the leadership-role is to create, sustain and communicate the conditions required to achieve the organisational unit’s desired outcome at minimal risk [4].

When it comes to K2K Emocionando helping transforming organisations, Koldo Saratxaga says the following about leadership:

- Leaders should create an environment in which employees can excel — which aligns with the DFS definition of the leadership-role.

- Leaders have no power — In DFS leaders should create conditions, not make decisions, and thus are not in need of traditional hierarchical powers. In hierarchical organisations, however, managers who take on the leadership-role may still be “gatekeepers” of some sort. From DFS’ perspective this is not problematic, as long as these gatekeepers avoid decision making. Instead of managing by decision making they can e.g. manage by approval (see [6])

- Leaders don’t get extra salary — In an organisation without a hierarchy of note, and without job descriptions etched in stone, the compensation system requires a different approach. Most importantly, it must be transparent. From the perspective of DFS leaders may or may not get extra salary, as long as it is substantiated.

- Leaders merely co-ordinate and communicate with other teams — This is required to ensure the team can achieve its objectives at minimal risk. But coordination and communication with other teams alone does not create an environment in which employees can excel. This statement is at odds with the first one.

- Teams can spread the leadership-role across two or more people — The moment you take “decision making privileges” away from the leadership-role, then the leadership-role is merely a role and not a function. The leadership-role can thus readily be taken up by more than one person. To make this work the leadership-role must be well-defined.

- Teams can replace the leader at any time — Although it would be counterproductive not to replace someone who isn’t up to the task, this “rule” also indicates that there is decision making involved in selecting the leader in the first place. A support structure for team leaders (“advisors” who don’t have decision making power either) may be advisable.

K2K and Decision Making

In DFS a “decision” is a special type of choice: a choice which is not fully substantiated to contribute to achieving a desired outcome. To minimise decision making desired outcomes must be transparent and non-ambiguous, and expertise is to be utilised to fully substantiate as many choices as possible.

Koldo Saratxaga says the following regarding decision making:

- Top-down decision making was stopped — No hierarchical decision making.

- Every decision taken involves the people it affects — This will go a long way in ensuring that available expertise is optimally utilised. In DFS those choices which cannot be fully substantiated are to be at least considered for risk management.

- Decision-making must be shared — In DFS decision making is to be avoided first, minimised second, and the associated risk managed third. In the context of K2K Emocionando “sharing decision making” may be another way of saying that there is no such thing as hierarchical decision making. But “shared decision making” as e.g. advocated in healthcare tends to come down to distributing the responsibility of making the decision. It doesn’t avoid the decision, and it doesn’t minimise the associated risk either.

- For decision making it is crucial to have full transparency — Full transparency is what is needed to be able to fully substantiate a choice and thus minimise the risk it will not contribute to the desired outcome.

A summary of Koldo Saratxaga’s approach, on which K2K approach is based, is provided in Figure 5.

***

The rest of the article is available as PDF.