An original article by Decision Free Solutions

On experts and expert organisations

For the PDF file of this article click on the download-icon on the left-hand side of this page or simply click here.

Note to the reader: This article is a chapter of the manuscript with the work title “Achieve aims with minimal resources by avoiding decision making — in Organisations, (Project) Management, Sales and Procurement (Everybody can manage risk, only few can minimise it)”. The article refers to other chapters, but can be read on its own. Other chapters are “On Decision Making”, “How to predict future behaviour of individuals and organisations”, “The four steps of DICE that will change the world and “The five principles of TONNNO that will avoid decision making”.

Making expertise matter

That is what the approach of Decision Free Solutions aims to achieve: to make expertise matter. If expertise matters, including yours, work will become more fun, risks will be minimised, desired outcomes are much more likely to be achieved and against much fewer resources. As with “risk” and “decision”, it is important to also define the term “expert” before describing the principles and steps of the approach.

The Oxford Dictionary definition of an “expert” is “a person who is very knowledgeable about or skilful in a particular area”. This definition sounds reasonable enough, but it is also non-specific. When is someone to be considered “knowledgeable”, let alone very knowledgeable? As this book is all about “expert” and “expertise”, a more comprehensive definition is warranted.

Next to providing a comprehensive definition this chapter will also address other questions, such as “how, using what skills, does an expert minimise risk?” “Can anybody become an expert?” “Are there different types of experts?” And also, “What type of person would be ideal to help create a culture which allows experts to use their expertise?”

A comprehensive definition of the word ‘expert’

In the context of the concept of Risk Minimisation a comprehensive definition of the word ‘expert’ is the following:

The term ‘expert’ (noun/adjective) denotes the minimisation of risk in achieving a desired outcome through:

|

[spacer height=”20px”]

This definition:

- Is broad in its use, as it applies not only to an individual or collective of individuals (noun), but can also be used as an adjective to indicate that a certain entity is able to minimise risks in achieving a desired outcome (e.g. ‘‘an expert organisation”).

- Ties the use of the word expert to achieving a desired outcome: an expert is always an expert in-relation-to-something that is to be achieved.

- Identifies those as experts who are capable of substantiating choices (and thus able to avoid decisions).

- Also identifies those as experts who may not be able to entirely avoid decisions (because not all information is available or accessible), but are able to substantiate the assumptions made in coming to a decision.

- Identifies those who are able to identify decision making whenever and wherever it occurs as an expert (as this is a pivotal and required first step to avoid decisions and or to manage the associated risks).

- Is still in accordance with the Oxford Dictionary definition (an expert needs to be“very knowledgeable about or skilful in a particular area” to be able to substantiate choices and or assumptions made).

The expert and the specialist

So how does the proposed definition of “expert” differ from the commonly used one (as also found in the Oxford Dictionary)?

From the definition in the previous section follows that anyone able to minimise risk is an expert. Those who only identify decisions are also experts. They may direct others to come up with substantiations or request that the associated risk will be adequately managed. In this way board members, managers, project leaders and others without any specific in-depth knowledge of the field they work in can be experts.

Those who are able to minimise risk in a particular area generally are knowledgeable and or skilful in this area. They make substantiated choices, and when a decision can’t be avoided they will substantiate the assumptions they make in coming to the decision.

But not everybody who is knowledgeable and or skilful in a particular area will also automatically minimise risk. A specialist — “a person highly skilled in a specific and restricted field” — may also be able to minimise risk, but many a times doesn’t. Often specialists fail to oversee the entire process or project (they do not perceive enough information relevant to achieve a desired outcome), or they use technical terms and details in the communication with non-experts.

Experts typically are in need of specialists, ensuring the specialists substantiate clearly why they make the choices they do.

Organisations typically are in need of — and should employ — experts, whereas specialists are to be consulted or may be hired only when needed.

The word “expert” as used in this book differs, thus, from how the word is commonly used. In the approach of DFS any so-called expert who is unable to substantiate choices will not qualify as one. Any one who is able to identify decision making whenever and wherever it occurs would.

“Someone who is able to minimise risk in a particular area is generally also knowledgeable and or skilful in this area.” An expert plumber and an expert project leader may be examples of this. But what about expert consultancy firms, investment bankers, sport scouts, politicians and or historians (not to mention “expert decision makers”, the ultimate contradictio in terminis as far as this textbook is concerned)? Do these experts also minimise risk? Are they able to predict an event’s outcome? There is overwhelming evidence that they cannot. Hiring these experts — unable to demonstrate in an unambiguous way they were able to consistently achieve or predict outcomes — may very well be sensible, but it doesn’t minimise risk. Something some of these so-called experts may vehemently disagree with. If only because the combination of common sense/intelligence and knowledge is to account for something. That this is not the case has been irrefutably demonstrated by the works of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who started their collaboration in the early 70’s. Their first scientific paper, published in the journal ‘Cognitive Psychology’ in 1972, was titled “Subjective probability: A judgment of representativeness”. It describes the first of many so called “heuristics” or “simple rules governing judgment or decision-making”. In short, when something appears similar in characteristics to some known population, people (in general) tend to make the mistake of equating “more similar” with “more likely”. The fact that someone looks like a certain sport icon does not, in fact, make it more likely he or she will turn into one. The ability to spot similarities (i.e. based on accumulated knowledge) does not result in better predictions of what will happen. Another heuristic proposed by Kahneman and Tversky which is commonly found with experts is what has become known as hindsight-bias. In 1972 Irving Biederman, an associate professor of psychology at Stanford University, invited Amos Tversky to give a series of different talks, each aimed at a different group of academics [5]. “In his talk to the historians, Amos described their occupational hazard: the tendency to take whatever facts they had observed (neglecting the many facts that they did not or could not observe) and make them fit neatly into a confident-sounding story.” In Amos words: “This ‘ability’ to explain that which we cannot predict, even in the absence of any additional information, represents an important though subtle flaw in our reasoning. It leads us to believe that there is a less uncertain world than there actually is, and that we are less bright than we actually might be. For if we can explain tomorrow what we cannot predict today, without any added information except the knowledge of the actual outcome, then this outcome must have been determined in advance and we should have been able to predict it.” Which is what we generally can’t. And all the historians who attended Amos’ talk realised they had falsely prided themselves of exactly this ability: to construct, out of fragments of information, compelling explanations of events which then, in retrospect, seemed predictable. “And they left [Amos’ talk] ashen-faced”. In his quote Amos Tversky actually points out the difference between “experts” as defined by the Oxford Dictionary and “experts” as it used in this textbook: experts who can minimise risk can, to a certain extent, predict the outcome of an event. |

[spacer height=”20px”]

The Event model and what it says about experts

What are experts made of?

An expert or an expert organisation minimises risks by substantiating choices and assumptions and identifying the decisions which cannot be avoided as risks for further risk management. But how do you become an expert? What does it take? What are experts made of? How can they be identified? To begin to answer these question the Event model is used again.

Event conditions and universal rules

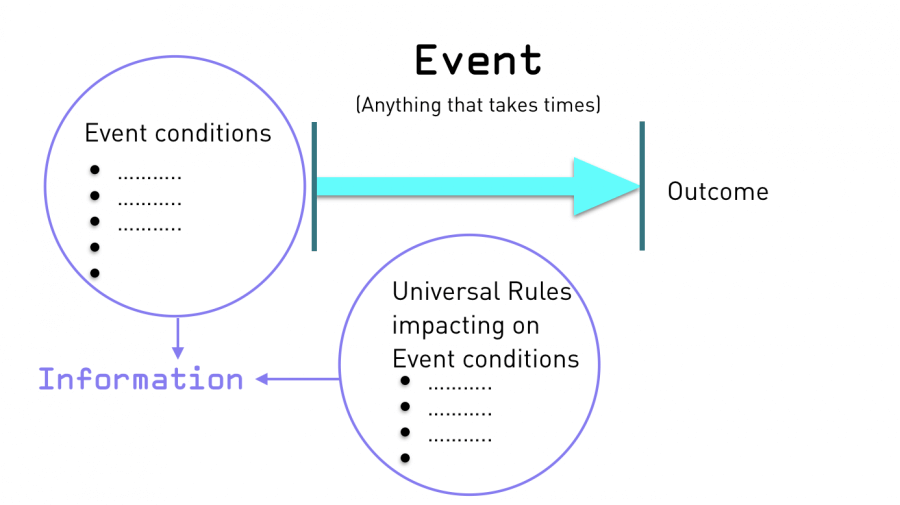

In the Event model an event is defined as “anything that happens which takes time” [1]. It can last a second, it can last years. Letting go of a helium filled balloon and a project to put people on the Moon are both events. The conditions at the end of the event are called the “outcome”.

Repeating what was said before, the Event model (see Figure 7) states that, at any point in time, an event:

- Has unique event conditions

- Is governed by unchanging universal rules which regulate how the event conditions change using a predictable logic.

- Has a unique outcome, which is the result of the application of universal rules on the event’s conditions.

Figure 7. The Event model including the definition of ‘Information’.

At any one time and in any one location there is a unique set of event conditions. Examples of event conditions are available expertise, financial resources, political chaos, tensions between colleagues, the weather. In short, anything that simply “is” at the time an event commences.

These conditions will be impacted upon by universal rules. Universal rules always exist and never change, and apply to everything (e.g. people, organisations, environment). These rules include the laws of physics as well as anything else which defines the change of a physical environment over time.

If you sow some seeds then, given the right conditions, something will grow out of it. This is a universal rule. There are countless universal rules. Over time food will perish. If somebody hasn’t changed his/her abusive behaviour for twenty years, then regardless of environment this behaviour will persist in the near future. If a politician skilled at manoeuvring him or herself to gain control or power becomes the chairman of the board of directors, then the focus of strategy will shift from the long to the short term. If you appoint cabinet positions based on loyalty rather than merit then desired outcomes will no longer be achieved. If a company lacks discipline and is run by a first-class jerk this will impact the quality of provided solutions.

It will be shown in the chapter “Predicting future behaviour” that many characteristics of a person or an organisation are linked, and that by observing certain characteristics other ones (which may be harder to observe) can readily be assumed. This too is a universal rule.

In the chapter “Risk” John Aaron (flight controller during the Apollo Program) was quoted as saying that “a unique set of circumstances” resulted in the success of the Apollo program, meaning that this outcome could not be simply reproduced today by giving something enough priority and money. A crucial event condition mentioned before was the particular culture of the Langley Research Center, which resulted in a range of creative solutions to challenging problems. Another example of the importance of the right event conditions in achieving an outcome concerns the mere availability of the ingenuity and engineering skills. Something the Apollo program needed in abundance. Turns out many of these kills simply happened to be available because of unrelated events. One event was the missile-based nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union which had already started during the Second World War. The United States obtained much needed expertise simply through capturing German missile technology as well as their personnel. This technology and personnel went on to play a crucial role in the Apollo program. As did more than a thousand highly skilled Canadian engineers. They had been working on the most advanced interceptor aircraft: the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow. The Arrow is considered to have been an advanced technical and aerodynamic achievement for the Canadian aviation industry, holding the promise of near-Mach 2 speeds at great altitude. It was intended to serve as the Royal Canadian Air Force’s primary interceptor in the 1960s and beyond. Until their government abruptly halted the project in February 1959 and many of its engineers ended up making invaluable contributions to the Apollo program. Source: Wikipedia, [2] |

[spacer height=”20px”]

Information

From the Event model — and in line with the principle of causality — follows that the outcome of an event is predetermined (fixed) by the combination of the event’s conditions and universal rules. This combination of event conditions and the universal rules impacting on these conditions is called “Information” (see Figure 7).

IMT states that there are no “random” processes at work (nobody is throwing dice), and that “information” is simply always there. It only has to be perceived. And if you are able to perceive all an event’s information, then you predict the outcome of an event: you can look into the future.

We all can look into the future. If someone is holding a balloon filled with helium and lets go of it we know what will happen. When asked to catch it we will quickly reach for it and try to get hold of it before it is too late. That is because we can oversee all the event’s conditions and we are all experts in gravity and helium-filled balloons. Ergo, we perceive all the event’s information.

Experts achieve desired outcomes

In everyday situations which are more complex, there will be no one who can accurately perceive all an event’s information. But those who perceive a lot of an event’s information, and who are thus able to foresee, with a certain degree of likelihood, what the outcome is going to be, are “experts”. Risks are further minimised by the expert by acknowledging when certainty stops and assumptions need to be made. In such a case the expert will substantiate assumptions made and identify the decision as a risk to be considered for Risk Management.

As stated before, in a worldly context, we are often interested in achieving a particular desired outcome. An expert has been defined as someone who is able to minimise risk in achieving a desired outcome. An expert is not merely able to perceive the current event’s information, but will also know how to alter the event’s conditions so that the desired outcome can be achieved. The better the expert, the higher the probability — and the fewer additional resources will be required — to achieve this desired outcome.

When I became the project leader of the Amsterdam Proton Therapy Center (APTC) I had more than a decade of experience in both project management and proton therapy. What I didn’t have any experience with was the configuration of two university hospitals and a comprehensive cancer center — with no history of successful collaboration — collaborating. The project had to take many hurdles, and it took them one by one. Then, about two years into the project, the most transparent, forward-thinking and sympathetic board member was about to retire. In his last steering group meeting he mentioned that, for his hospital, getting the green light from all of the various councils and supervisory boards to agree with the financial proposals would be problematic. This was stating the obvious, and true for all of the hospitals. But the fact that it was him who now used the word “problematic” — instead of “challenging” or “difficult” — makes me remember this moment to this day. It was an ominous word, indicating a change in the hospital’s position that was to result in the unilateral and unexplained suspension of the project one and a half year later. I had perceived this one bit of crucial information, but I was still clueless about the universal rules that were at work in the background and which had resulted in this change of the event’s conditions. With the departure of this board member the hospital had replaced the entire board within a short period of time. But perhaps more crucially, the new chairman of the board who had been appointed only a few months before was a former politician. Someone with a very public profile, a columnist in a major newspaper, and with a regular presence on national television. Someone, too, who had no qualms with taking credit when it wasn’t due, who had left his previous work circles behind in disarray, who shunned commitment and accountability, and whose focus was strictly short-term. In the role of project leader I was to learn that politicians are likely to be poor managers in organisations in need of long-term strategies, and that they are perfectly able to present the irrational as common sense. Without support in the one hospital’s new board — which saw no value in upholding prior commitments and shifted its focus to achieving short term gains — the project’s desired outcome could no longer be achieved. Eighteen months of trying, pulling, pushing, and even one of the other hospitals proposing to absorb all of the project’s financial risk, couldn’t change this new outcome. The universal rules distilled from the event are that an entirely new board is likely to re-prioritise an organisation’s ongoing activities (and is thus to be considered a project risk). That a politician-board member with a history of non-commitment will not feel bound by the organisation’s prior commitments (not even when they align with the organisation’s strategy). And finally, that given a (new) set of event conditions, and given the universal rules at work, you can’t manage, control or influence the event’s outcome into something else. |

[spacer height=”20px”]

You can download the complete PDF here. This PDF includes the following sections which are missing here:

- How to become an expert

- Perceptiveness and experience

- The Cycle of Learning

- Types of expert

- The types of expert diagram

- Inexpert, the Perceiver, the Experienced Perceiver, and the Skilled

- Types of Information Environments

- The Information Environment-Diagram

- To utilise expertise an organisation needs “Decision Free Leaders”

- How to identify the expert?

- Are you an expert?

- References