An original report by Decision Free Solutions.

Decision Free Procurement

Shown here are the first couple of chapters of the report “Decision Free Procurement — A method to procure and utilise the best available expertise to achieve the desired outcome”. The full report is available as PDF [here].

Note to the reader: The method of Decision Free Procurement is the result of applying the approach of Decision Free Solutions to the field of procurement. With“procurement” is meant both the identification of the vendor and the delivery of the product/solution with which the desired outcome will be achieved.

This document assumes a familiarity with (or access to) the approach of Decision Free Solutions (DFS), including the four steps DICE , the five principles of TONNNO, the concept of the Decision Free Leader (DFL) and the definitions of “risk”, “decision” and “expert”.

About DF Procurement

Introduction of DFP

In Decision Free Procurement (DF Procurement or DFP) there is an owner who is in need of help to achieve a desired outcome. This help comes in the form of expertise and will be provided by a vendor. DFP is the resulting method when applying the approach of Decision Free Solutions (DFS) to achieving the desired outcome by way of procuring expertise. Procurement here thus refers to both the identification of a vendor and the delivery of the vendor’s solution.

DF Procurement is one of several methods developed by applying DFS to a particular field. DF Procurement is of particular interest, as by definition procurement involves two organisations with different expertise who have to communicate and collaborate in a high-stakes environment (e.g. achieving organisational aims, financial risks, reputation). To create transparency in such an environment is as challenging as it is rewarding. The method of DFP is thus an example of how to communicate in a very complex situation, which at the same time is very common: all organisations need to procure products and solutions and have them delivered against minimal risk.

The definition of DFP — annotated

DF Procurement is a method to procure and utilise the best available expertise to achieve the desired outcome against minimal risk |

This definition communicates the following:

- Despite its name, the method is not “a procurement tool”. The method is of no value to anyone when expertise is merely procured but then not utilised. If DFP is run by a procurement department and then “handed over” to the operational people who have to assist, support and or collaborate with the identified vendor failure is all but certain.

- No assumptions are made as to where or with whom expertise resides. The one who looks for expertise to achieve a desired outcome almost invariably also possesses expertise which is essential in achieving this desired outcome. In fact, as will be explained in the next section, an organisation that possesses no expertise will not be able to run DFP successfully.

- The method does not assume “a perfect match” between the expertise that is desired and the expertise that is available. In fact, it may well be that “the best available expertise” is still lacking in several important areas. The identified “expert vendor” may still show characteristics which are not fully aligned with expert-behaviour as identified by the EXPID model. This only means that the owner has to be aware, maybe even vigilant, the identified vendor may still make assumptions or other types of decisions. The EXPID model is of great importance in assessing the presumed level of expertise. This information is to be put to use in the Clarification step where any type of decision making is to be “uncovered” before the delivery of the solution is to begin.

- What is procured is “expertise” and not merely a solution. Expertise includes a solution (usually in the form of one or more products and or services), but also the knowledge required to deliver it in a given and often unique situation.

- The expertise procured and utilised is to achieve a desired outcome. The desired outcome is thus what is used to identify the best available expertise, and at the same time is what the identified vendor is to work towards. This makes its pivotal that the desired outcome is transparent and understood the same by all involved.

- DF Procurement, like all methods following from the application of the approach of Decision Free Solution, is a method to minimise risk. The risk minimised is resource risk and outcome risk. The greater the risk in achieving the desired outcome — the greater the need for the use of expertise — the greater the potential benefit of using DF Procurement.

- The organising principle of the method is the avoidance unsubstantiated choices, also known as decision making. It applies everywhere. All the time.

Expert vendors select their owners, who compete with other owners

An owner in need of expertise is competing with other owners for this same expertise. The vendor in possession of this expertise will select the owner that will allow it to make optimal use of its resources. Profit is the result of delivering solutions quickly and successfully, not from contract clauses, extra work and inefficiency.

An expert vendor will not participate in a tender when it becomes clear the owner can not transparently define what it is it is in need of. An expert vendor will recognise any decision making from the owner’s side, be it in its past behaviour, during the market exchange or during other interactions, or at the very latest in the procurement documents. There is no point in running a DFP tender as a non- or sub-optimally-performing organisation. It will become a flawed process aimed at identifying vendors who aren’t experts to begin with.

DFP is a method by experts for experts

When an organisation sets out to procure and utilise expertise it is sending a strong signal to the expert-vendors that their expertise will be welcomed with open arms.

The promise of DFP for the owner is that — given the current availability of vendor expertise — the desired outcome will be achieved against minimal risk, with the highest available quality and often for the lowest price2.

The promise of DFP for the vendor is that — given the ability of the owner to run DFP successfully throughout — it can fully exploit its expertise against the highest margins as it will not be bogged down by an owner who tries to exert control over the process and thus lowers the expert’s productivity by wasting its valuable resources.

Not every organisation is able to create the conditions for a vendor to utilise its expertise. In fact it takes an expert organisation to accommodate expert vendors. In very much the same way an expert organisation that runs DFP well will never end up with a non-performing vendor, an expert vendor will never consider wasting its valuable resources on an organisation that fails to run DFP correctly.

The better an owner sets up a DFP tender, the greater the expertise it is able to attract. The better DFP is run, the more and more efficiently risks will be minimised. The performance of the owner and the performance of the vendor are correlated. In its purest form DFP is a method by expert organisations for other expert organisations. There is only one way to execute the DFP method, and that is to execute it successfully.

The owner, the vendor and the desired outcome

The desired outcome may be achieved by the vendor in full, or the vendor is merely to contribute to it (e.g. as part of a supply chain). Generally the owner is a part of this supply chain in the sense that it is in need of external expertise, a product, a service with which it can utilise its own expertise to achieve the desired outcome. No matter what the situation is the owner is to define the desired outcome, and not merely an aspect of it. The owner is, logically, not to prescribe the part the expert is to provide. And the vendor is to utilise its expertise to contribute to achieving the desired outcome, and not to an isolated aspect of it.

From this also follows that the vendor may contribute to achieving the desired outcome, whereas the desired outcome itself will be achieved only later (either in a supply chain context or because the owner was in need of external expertise in order to achieve the desired outcome). Having said all that, for clarity and brevity it is assumed here that the desired outcome will be achieved once the vendor’s plan has been executed. In practice this will often be achieved in a collaboration between vendor and owner, both providing their own expertise.

What is it the owner buys?

How the vendor’s expertise (and product or service) will achieve the owner’s desired outcome the vendor clarifies by way of a plan. Only when it is transparent to the owner that with the vendor’s plan the desired outcome will be achieved will the vendor be awarded and can a contract be signed.

It is important to realise that in DF Procurement the owner doesn’t buy a product or service: a product or service with which the desired outcome cannot be achieved is worthless to the owner. The owner doesn’t buy the desired outcome either: the outcome may not be concrete enough (impossible to say for certain when it is achieved), or be something that cannot be achieved because of reasons out of the vendor’s control. The owner, in essence, buys the vendor’s plan and with it the plan’s outcome.

The vendor’s plan contains all of the vendor’s expertise, and includes the delivery of a product and or service, with which the desired outcome is to be achieved. If, to the owner, the plan’s outcome — as has been been made sufficiently transparent by the vendor — is in accordance with the desired outcome, then the owner will sign off on it. The owner has bought the plan and with it the plan’s outcome.

What to do when the plan changes?

This plan, and thus the plan’s outcome, may change. Whenever a risk occurs the plan needs to be adjusted. This may have financial consequences as well as consequences for the plan’s outcome. The financial consequences are to be carried by the vendor if the risk occurring is an internal risk, and by the owner if it is an external risk. This is an incentive for both the owner and the vendor to make sure the plan is fully understood, that it is non-ambiguous who is responsible for what, and that the most important risks are identified and mitigated. Any change made in the plan must be substantiated with the desired outcome in mind.

What to do when the desired outcome can no longer be achieved?

Sometimes a risk occurs that is such that the plan’s outcome no longer can be brought fully in line with the desired outcome (e.g. some deadline will be missed, some functionality will be missing). In the agreement between the owner and the vendor how to proceed in such a situation is to be described and, alas, agreed upon. Here a distinction needs to be made between an internal risk or an external risk causing this situation. How to determine whether a risk is an internal risk or an external risk, and how to proceed when vendor and owner can’t agree on this, are also to be described in the agreement.

When to use DFP, and how does it differ from traditional approaches?

DF Procurement is a method which can be used in any procurement situation, both private and public. It is not an alternative or addition to the existing public procurement procedures, but can be used in any type of procurement procedure3. DF Procurement can be used when considering only one vendor, or when a choice has to be made between several vendors. In this text it is assumed the owner uses a tender, but it is not a prerequisite to use DFP. [As a consequence of this assumption the documents the owner provides will be referred to as “procurement documents” and the documents the vendors provide as “tender documents”].

DFP’s benefit or value is the greater the greater the risks and the consequences of something going amiss. DF Procurement is to be seriously considered when selecting a non-performing vendor is likely to result in considerable cost overruns and delays, and potentially in not achieving the desired outcome at all.

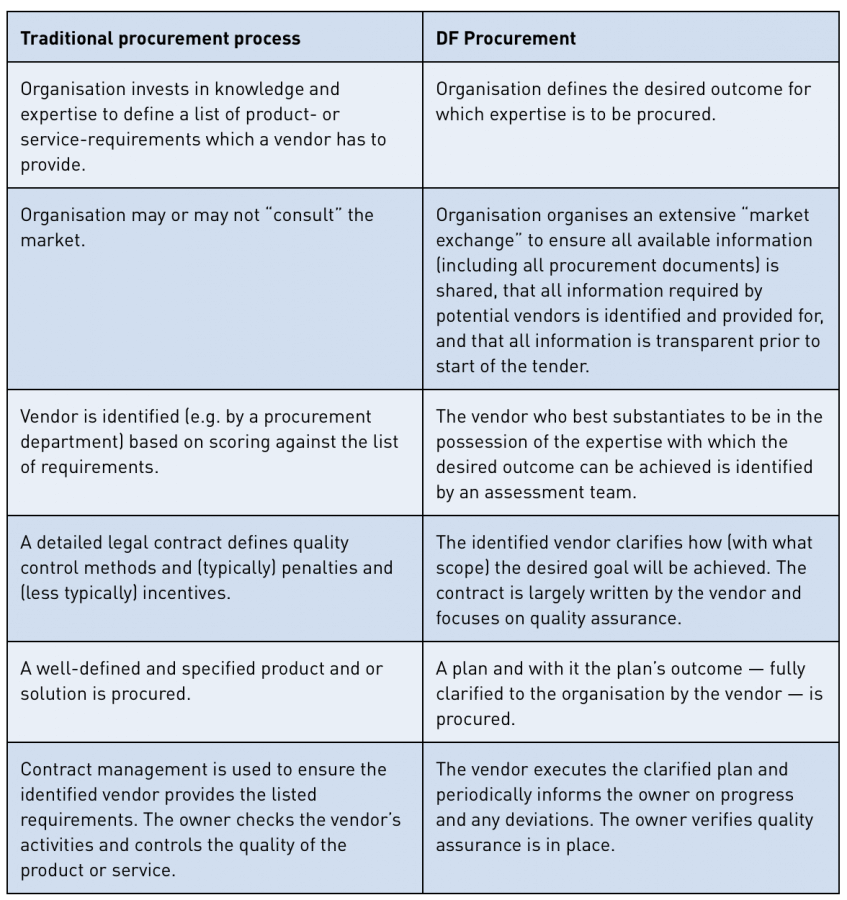

There is no such thing as a standard procurement process, but many procurements processes follow the template as shown in Table 2. These “traditional” processes involve the definition of requirements by the non-expert owner and the subsequent reliance of a legal contract to “force” the identified vendor to perform. Procurement tends to be an organised process run by procurement specialists, and then handed over to the part of the organisation that needed the procured product or service.

DF Procurement differs in that it does not define requirements and that its focus is not on a contract but on the actual achievement of the desired outcome (see Table 2). Also, there is no “handover” from one step to the next, as there will be employees who will be involved from the beginning of the tender until delivery is completed.

Because of this different approach DF Procurement has considerable advantages over traditional procurement strategies when a) the owner is in need of expertise it knows little to nothing about, and b) the actual delivery of the product or service is complex (and thus prone to delays and cost overruns).

Table 2. Direct comparison between ‘traditional’ procurement and DF Procurement processes.

Between 1960 and 1966 NASA’s budget went from $400 million to $6 billion, and in this time the number of contractors went from 30’000 to 360’000. Such growth could have led to large scale embezzlement. Many contractors may have made quite a bit of money, but no scandal of note was reported over the duration of the Apollo Program. The closest thing to an out-and-out scandal concerned a procurement process: the way North American got the contract to build the spacecraft. The manipulation of this process, I propose, may be considered the root cause of the Apollo 1 disaster. Joe Shea was in the middle of all of it. In November 1962 it was determined that astronauts would be going to the Moon using the lunar-orbit rendezvous concept. A spacecraft — to be made by North American — and a smaller lunar lander would travel to lunar orbit and the lander would land on the Moon and then re-dock to the spacecraft before being discarded. In November 1963, one year later, Joe Shea found that there was still no design for a command and service module compatible with lunar-orbit rendezvous. He found it hard to understand. What was happening? North American wasn’t performing. Ultimately this lack of performance would results in lives lost and the end of Joe Shea at the Apollo Program. North American, it turned out, was only one of five companies that had submitted proposals. They were rated last. Still they got the contract. What happened? The short version is: decision making. The longer version (of how they got contracted and what the consequences of using decision making in procurement for the Apollo program were), will be told in this chapter. Source: [2], Wikipedia |

DF Procurement in summary

DF Procurement Definition Step

At the end of the Definition step:

|

Owner activities:

- Prepare the DF Procurement event

- Define, to the best of the owner’s ability:

- The desired outcome

- The deliverables

- The event conditions

- The universal rules pertaining to the owner’s organisation

- Define the owner’s expertise and perceived role in achieving the desired outcome

- Draft the procurement documents, including:

- Required tender documents (type, length)

- Description of scoring process (method, communication)

- Market exchange:

- To ensure the desired outcome is unambiguous

- To actively solicit for any additional information which could be provided with respect to the event conditions and universal rules

- To inform, explain and educate the market with respect to the method of DF Procurement

- To obtain feedback on the draft procurement documents

- To observe the vendor’s characteristics

Vendor activities:

- Ensure the desired outcome, and the role of the owner in achieving it, is fully understood

- Assess the owner-specific event conditions and universal rules

- Ensure the draft procurement documents are transparent and complete

- Ensure relevant performance data in support of being able to achieve the desired outcome is or will become available

DF Procurement Identification Step

At the end of the Identification step:

|

Owner activities:

- Publish procurement documents

- Resolve any remaining issues vendors may have pertaining to the documents

- Score the tender documents

- Rank the vendors

- Communicate score and rankings

- Provide evaluation of identification procedure

- Perform the “expert verification check”

Vendor activities:

- Ensure final procurement documents are fully transparent

- Provide tender documents

- Make optimal use of the evaluation as provided by the owner at the end of the Identification step

- Prepare for the “expert verification check”

So how was North American awarded the contract to build the spacecraft (more specifically, the Command and Service Module (CSM))? During the Apollo Program the U.S. government used a standard procedure to award large contracts. It published a Request for Proposals (RFP) describing the work to be done. The contract was awarded based on a prearranged formula that weighed among others the technical approach, the personnel the bidder will use, and the bidder’s corporate expertise. The received proposals were rated by the various subcommittees of NASA’s Source Evaluation Board (SEB). The RFP for the CSM was published late July 1961. Five companies submitted proposals: Convair, General Dynamics, Martin, McDonnell, and North American. NASA’s SEB met October 9, 1961. North American was rated 5th by the subcommittee evaluating administrative capacity, 5th by the subcommittee on business criteria, and 5th by the subcommittee evaluating technical approach. But all of the subcommittees were then asked by the acting manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office to consider more criteria and to rescore. For one, they were to give more weight to the bidder’s experience in producing experimental aircraft. This rescoring exercise helped North American considerably since they had just built the experimental X-15, which in its initial flights was proving to be an exceptional aircraft. In “technical qualification” North American now edged Martin, but overall Martin was still first with North American tied for second with Convair. The SEB was unequivocal in its recommendation: “The Martin Company is considered the outstanding source for the Apollo prime contractor.” But rescoring wasn’t the only funny thing that happened with the CSM contract. In those years North American seemed to be able to rely on strong relationships with key people in the organisation (at one point a senior executive of North American was overheard threatening to have the Director of one of NASA’s offices fired if they were not allowed to bid for the lunar module). Someone on the CSM review panel thought the bidding process was all a waste of time as North American was going to win regardless of the score. He was not the only one thinking this way. Or trying to make this happen. Once James Webb received SEB’s recommendation and asked a series of managers (among others the NASA’s Associate Administrator and Deputy Director and the directors of the Office of Manned Spaceflight and of the Manned Spacecraft Center) whether there were, perhaps, other factors to be taken into account. And so, despite Martin coming out ahead, even after a rescoring exercise that heavily favored North American, North American was awarded the contract following a weekend of James Webb sleeping it over. It was awarded because several people who were not involved in the evaluation process considered a spacecraft an outgrowth of a more conventional flying machine. Thus they favored a company able to build an experimental flying machine, the X-15. In doing so they mistook a company able to build complex machinery for a company able to minimise risk in building entirely new complex machinery in a completely different environment, both literally and figuratively. Tensions between NASA and North American started the night of the award and would not fully end until 1968. In between three astronauts lost their lives (and Joe Shea his mental health). During Apollo 1’s launch rehearsal test on January 27, 1967, the Command Module caught fire. In the end nobody got blamed for the fire. Based on a series of observations — observations which will be shared next — it becomes clear, however, that North American’s culture was incompatible with minimising risk. A serious accident involving North American was written in the stars. A consequence of using decision making in procurement. Source: [2], Wikipedia |

DF Procurement Clarification Step

At the end of the Clarification step:

|

Owner activities:

- Accommodate the vendor in making it transparent that the vendor will be able to achieve the desired outcome

- Ensure that it is, indeed, transparent to all involved that the vendor will achieve the desired outcome — and when the vendor fails to do so: exclude vendor and start process with the vendor who ranked just below this vendor

- Conclude the agreement and inform the other vendors

Vendor activities (following the owner’s verification step):

- Clarify to the owner how the desired outcome will be achieved using all or some of the following:

- Summary of products and or solutions to be provided (scope)

- An outline plan from-beginning-to-end (defining the plan’s outcome) as to how the desired outcome will be achieved

- A milestone schedule including key performance indicators

- A risk management plan

- Verification and commissioning procedures

- Quality Assurance procedures

- Clarification step report

- Executive summary of main points

DF Procurement Execution Step

At the end of the Execution step:

|

Owner activities:

- Evaluate the vendor’s periodic progress reports

- Execute the owner’s activities according to the plan and provide the vendor with periodic progress reports on these activities

Vendor activities:

- Execute the vendor’s activities according to the plan

- Provide the owner with periodic progress reports, including occurring risks and deviations to the plan, how they may affect the desired outcome, and how they will be mitigated

- Evaluate the owner’s periodic progress reports (if utilisation of owner’s expertise is part of the plan)

- Collect performance information

If you want to read the rest of the report download the PDF file (or send us an email).